Living well with incontinence

If incontinence would be a country, it would be the third largest country in the world.

Caring for someone with incontinence can also be burdensome for the caregivers, regardless of them being family or professional workers. Almost a third of all people that care for an elderly relative, care for a person who has incontinence.25 This condition often becomes a psychological burden on the caregiver, as it takes up their time round the clock.26 The prevalence of incontinence in long-term care facilities is estimated between 50-80%,27 and one of the most common reasons for a person to move to a long-term institutional care28.

71%

worry about not being able to go to the toilet on their own as they get older or ill

67%

worry about not being able to care for their personal hygiene

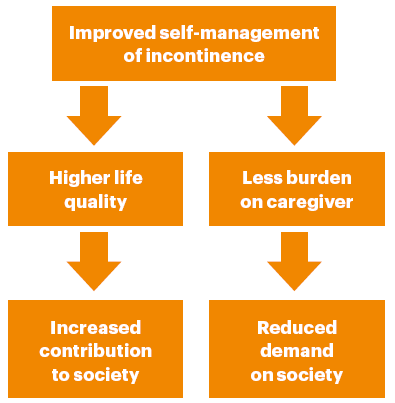

Consequently, poorly managed incontinence can have a large impact on both the quality of life of people affected and on societal costs. One Dutch study estimated yearly healthcare costs to 7,402 euro per patient, and societal costs to 3,811 euro per patient.29 The total costs are likely to rise as the number of individuals affected by incontinence increases. Enabling more people to manage their incontinence in a, for them, more suitable way, will both improve the life quality of patients, reduce costs and make better use of caregivers’ time.

Today, we have a better understanding on how to manage incontinence, and what good continence care looks like in order to improve it. The Optimum Continence Service Specification (OCSS) is a modular guide on how to best care for individuals with incontinence, which was developed by a multidisciplinary expert panel and presented to the Global Forum on Incontinence. A recent analysis estimates that implementing the OCSS could lead to significant benefits both for the individual patients and for society. The study looks at the potential effects for The Netherlands and estimates that the costs related to incontinence could be reduced by 31 million euro in the healthcare sector, and a total of 125 million euro in societal expenses over a three-year period. In the future the benefits might even be larger given the ageing population. By 2030, applying the OCSS may lead to savings between 32-75 million euro in healthcare costs, and 182-251 million euro in societal costs over a three-year period, while simultaneously yielding large health benefits in elderly communities (estimated to 2,592-2,618 in Quality-Adjusted Life Years*).30

By 2030, applying the OCSS may lead to savings between 32-75 million euro in healthcare costs, and 182-251 million euro in societal costs over a three-year period.

Several actions must be taken in order to achieve these results. First, we must raise the awareness of incontinence to ensure that more people affected dare to talk about their experience and seek help.31 Second, we need to ensure adequate pathways to navigate in the healthcare system, so that incontinence cases can be detected and assessed.32 Third, we must strive for an individualized continence care, where patients’ needs are responded to, and where they can influence the care as well as the solutions to use.

22 Global Forum on Incontinence, ‘About Incontinence’, http://www.gfiforum.com/incontinence, accessed 16 January 2018.

23 S. Schultz & J. Kopec, ‘Impact of chronic conditions’. Health Reports, vol. 14, no. 4, 2003, pp. 41-53.

24 A. Grimby et al., ‘The influence of urinary incontinence on the quality of life of elderly women’, Age Ageing, vol. 22, no. 2, 1993, pp. 82-89.

25 Estimate by Essity.

26 I. Appleby, G. Whitlam & N. Wakefield, Incontinence in Australia, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Canberra, 2013; R. Van der Veen et al., Quality of life of carers managing incontinence in Europe, 2011.

27 F. Leung & J. Schnell, ‘Urinary and fecal incontinence in nursing home residents’, Gastroenterol Clinics of North America, vol. 37, no. 3, 2008, pp. 697–x; J. Jerez-Roig et al., ‘Prevalence of urinary incontinence and associated factors in nursing home residents’, Neurourol Urodyn vol. 35, no. 1, 2016, pp. 102-107.

28 I. Milsom et al., ‘Epidemiology of Urinary Incontinence (UI) and Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (LUTS), Pelvic Organ Prolapse (POP) and Anal Incontinence (AI)’, in P. Abrams et al., Incontinence, 5th Edition, ICUD-EAU, Paris, 2013, pp. 15-107; P. Thomas et al., ‘Reasons of informal caregivers for institutionalizing dementia patients previously living at home: The Pixel study’, International Journal Geriatric Psychiatry, vol. 19, no. 2, 2004, pp. 127-135.

29 M. Franken et al., ‘The increasing importance of a continence nurse specialist to improve outcomes and save costs of urinary incontinence care: an analysis of future policy scenarios’, BMC Family Practice, vol. 19:31, 2018.

* The Quality-Adjusted Life Years (QALY) is a measure of disease burden, including both the quality and quantity of life lived. One QALY equates to one year in perfect health.

30 M. Franken et al., ‘The increasing importance of a continence nurse specialist to improve outcomes and save costs of urinary incontinence care: an analysis of future policy scenarios’, BMC Family Practice, vol. 19:31, 2018.

31 A. Wennberg et al., ‘Lower urinary tract symptoms: lack of change in prevalence and help-seeking behaviour in two population-based surveys of women in 1991 and 2007’, BJU International, vol. 104, no. 7, 2009, pp. 887-1039; C. Shaw et a., ‘A survey of help-seeking and treatment provision in women with stress urinary incontinence’, BJU International, vol. 97, no. 4, 2006, pp. 752-757.

32 A. Wagg et al., ‘Developing an Internationally-Applicable Service Specification for Continence Care: Systematic Review, Evidence Synthesis and Expert Consensus’, PLoS ONE, vol. 9, no. 8, 2014, e104129.