Empowering women by making their needs count

“When I am at work, it can be really difficult to manage my period as there are often no bins to dispose sanitary napkins. I have to find other solutions and it can be really awkward if you are carrying something around. My friend who works in a different building complains that there is only one restroom to use and it is ten minutes away. Sometimes she waits too long to go and there is a mess, or her boss is annoyed when she is away from her desk for a long time.”

Catherine, Administrative Assistant, Kenya

The global movement towards gender equality has seemed like a steady, albeit slow moving train. However, last year we witnessed not only a halt, but a step backwards. According to the World Bank, which has measured the global gender gap since 2006, the overall global gender gap will now take 100 years to close rather than the estimated 83 years in 2016.7 It will take more than three generations8 until a baby girl is born with the same possibilities as a boy to realize her human rights.

Nonetheless, there are still some bright spots. According to the World Bank data, countries like Namibia, Nicaragua and Rwanda have managed to challenge societal structures in a relatively short period of time, making strides towards closing the gender gap. We also see more and more countries establishing their own ministries of gender equality in order to overcome the obstacles that have long held women back.

One significant obstacle that leaves many women at a disadvantage is the common perception and stigma of menstruation. At any given moment, every fourth woman of menstruating age in the world is on her period. For those who have the means to manage it, this does not prevent them from going about their normal lives. Women who menstruate need a private space for washing and managing their menstruation, sanitary products to absorb the blood, and the ability to dispose of sanitary materials.9 These needs are overlooked far too often,10 making menstruation an impediment in community participation, education and working life.

Even when they have the means and knowledge to manage their periods, menstruation stigma can put women at a disadvantage. A U.S. study called “The Tampon Experiment” clearly illustrates that being reminded that a woman is menstruating affects the perception of her competence and likeability. In this experiment, participants interacted with a female actor, who pretended to be a participant and seemingly accidentally dropped either a tampon or a hair clip. Dropping the tampon led to a lower evaluation of the actor’s competence and decreased her likeability.11 The fact that the same effect did not appear when dropping a hair clip – an object strongly connected to femininity – shows that the effect was not due to the fact that participants are reminded of the actor’s gender. It rather demonstrates their paradoxical perception of menstruation as something that is unfeminine and impure, even though it is a sign of health. Women who are not able to conceal their menstruation are seen as lacking control over their bodies.12

Being reminded that a woman is menstruating affects the perception of her competence and likeability.

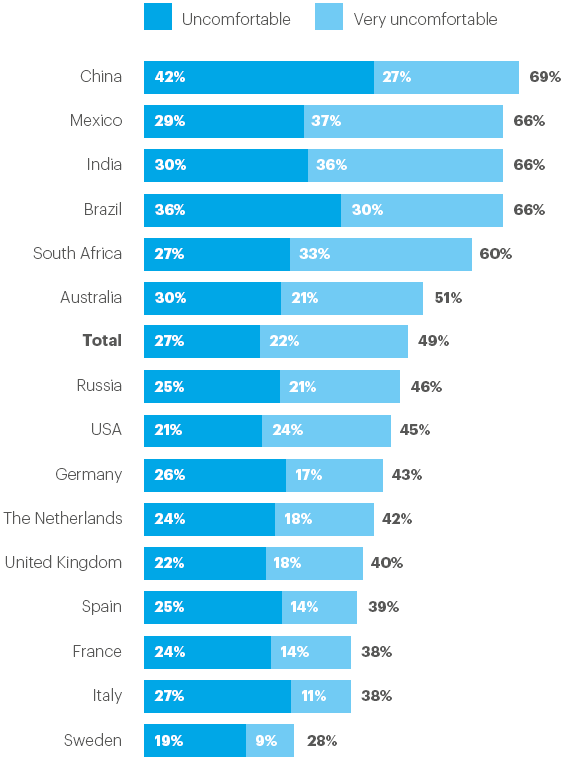

The consequences of these perceptions are visible in Essity’s global survey. Nearly half of the female respondents experience social discomfort during their period. The social stigma around menstruation is especially strong in countries like China, Mexico, India, and Brazil where two out of three female respondents feel uncomfortable in social situations during their menstruation.

Periods perceived as a woman’s business

73%

of mothers

40%

of fathers

have talked to their daughter(s) about menstruation

32%

of mothers

30%

of fathers

have talked to their son(s) about menstruation

The silence around menstruation has costs for the individual woman and for society as a whole. For instance, many women lack the menstruation health literacy to tell whether the pain or other symptoms they experience in relation to their menstruation cycle are normal. Consequently, they wait too long to seek help,13 and once they do, they can be misdiagnosed.14

Over the last few years, however, we have witnessed a movement to break the stigma of menstruation. Women and men around the world are speaking up about menstruation and the needs periods present. These menstruation activists are paving the way for a future where menstruation is considered a normal bodily function and discussed openly. They show us that changing the way we deal with periods is necessary to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals of ensuring women equal access to sanitation (SDG 6.2) and empower women (SDG 5). When women’s needs are taken into account, we build a society where women have the same opportunity to realize their basic human rights and close the global gender gap.

In this chapter, we will explore why it is important to look at menstruation from a human rights perspective, how lack of good sanitation facilities put working women at a disadvantage, why menstrual health literacy is essential for improving women’s health, and how different actors are working towards breaking the taboo of menstruation.

“Menstruation is inherently neither controversial nor political. It is a normal and healthy part of girls’ and women’s biology, and should never be used as a basis for discrimination, inequality or harm.”

Michelle Milford Morse, United Nations Foundation

7 World Economic Forum, The Global Gender Gap Report 2017, 2017.

8 Assumed that a generation length is 30 years.

9 I. Winkler. & V. Roaf, ‘Taking the Bloody Linen out of the Closet: Menstrual hygiene as a priority for achieving gender quality’, Cardazo Journal of Law and Gender, vol. 21, no. 1, 2014, pp. 1-37.

10 K. Anthony & M. Dufresne, ‘Potty Parity in Perspective: Gender and Family Issues in Planning and Designing Public Restrooms’, Journal of Planning Literature, vol. 21, no. 3, 2007, pp. 267-294.

11 T. Roberts, J. Goldenberg, C. Power & T. Pyszczynski, “Femenine Protection”: The Effects of Menstruation on Attitudes Towards Women’, Psychology of Women Quarterly, vol. 26, no. 2, 2002, pp. 131-139.

12 I. Winkler. & V. Roaf, ‘Taking the Bloody Linen out of the Closet: Menstrual hygiene as a priority for achieving gender quality’, Cardazo Journal of Law and Gender, vol. 21, no. 1, 2014, pp. 1-37.

13 Nawroth et al., in Richter, B., Richter, K., Endometriose: Aktuelle aspekte der histo-pathologischen und molekularpathologischen diagnostik 2, 2013.

14 Interview with Sally King conducted 2018-02-22.